"Los

Ángeles, ciudad de eterna primavera, tiene cuatro estaciones: temblor de tierra,

incendio, inundación y sequía"

Dicho popular

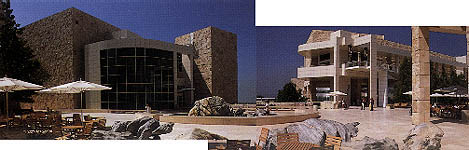

Para algunos el Centro Getty, recostado sobre las colinas de Santa Mónica

y con la autopista a San Diego serpenteando a sus pies, se asemeja a un monasterio o a una

fortaleza. Puede ser. La imagen más usual que guardamos de un monasterio suele asociarse

con la de una estructura defensiva. No en vano, los monasterios, en su apogeo, fueron

búnkeres que custodiaron la sabiduría: la ciencia y el arte. El complejo museístico del

Getty Center no es más que eso: unas cuantas cajas fuertes que atesoran estos

bienes un milenio después. Un centro de exposición e investigación sobre el arte. A

este, como a aquellos recintos medievales, se accede por un angosto y empinado sendero que

parte desde la freeway I-405.

Sin embargo, se parece más a una "acrópolis" griega, con los

edificios dispuestos, aparentemente, al libre albedrío, contrastando con la naturaleza

del paisaje al oponer sus rectas y nítidas aristas, casi todas de raíz cúbica. Así

actuaron los arquitectos de tantos templos griegos, quienes, además, rodearon los

recintos sagrados con un perímetro de murallas que arrancaba de la roca desnuda. De modo

similar, el Centro Getty, constituido por una serie de pabellones diferenciados y un

jardín, se alza sobre taludes de travertino desbastado en medio del disperso bosque. Para

mejor metáfora piénsese en el color y la textura elegida por Richard Meier para el

acabado final. Piedra casi amarmolada en basamentos y volúmenes prismáticos, granito en

los suelos y sus características placas cuadradas blancas y beig, sin brillo, para las

envolventes. Se ha optado a propósito "por un sólido clasicismo" como imagen

simbólica para que las moradas de los dioses del siglo XX se posen sobre la tierra.

Aunque lo tradicional en el currículum de este master builder es su europea

modernidad, centrada en la revitalización de sus inicios heroicos.

Mientras los griegos adoraban a sus ídolos en los templos dispersos en el

interior de aquellos lugares de peregrinación, los ciudadanos americanos pueden admirar

la colección de arte europeo que se muestra en las distintas salas de esta "ciudad

ideal para la cultura". Probablemente, el gran Museo que ha construido el Getty

Trust, avistando la bahía desde Malibú hasta Venice, sea un santuario de nuestra

época en el que el arte ha sustituido a los dioses del Olimpo. Y no es esta una

afirmación gratuita. De hecho, según Mario Botta, autor del MoMA de San Francisco,

cualquier museo se podría interpretar "como un espacio dedicado a la búsqueda de

una nueva religiosidad". En su opinión "en la ciudad actual, el museo

desempeña un papel similar al de la catedral en siglos pasados". Y la catedral de

Los Ángeles no puede ser un hito aislado como el MoCA de Arata Isozaki u otros museos

confundidos en la inmensidad urbana. La catedral de la ciudad más extensa del planeta ha

de tener otra escala, la cual se corresponde con la de una acrópolis.

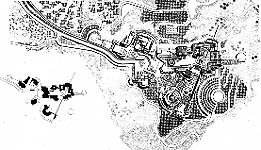

Partiendo de estas condiciones (representatividad, emplazamiento y

programa), el Centro Getty dispone sus edificaciones de un modo salpicado sobre dos mallas

ortogonales, giradas entre sí, que resultan un reflejo de las dos direcciones que toma la

autopista al curvarse bajo el enclave: la trama de Los Ángeles una, el paso de Sepúlveda

la otra. Esta sutil referencia sirve de excusa a la geometría ordenadora del complejo

cultural, en donde se despliega una colección de arquitecturas como si se tratara de un collage

en tres dimensiones. La propuesta resultante, tan ensimismada en su apariencia azarosa,

puede hacer pensar que Richard Meier se ha guiado por la metrópolis ya que, como afirma

Ann Bergren, "si la discontinuidad es la realidad urbana de Los Ángeles, lo realista

es diseñar edificios en forma de piezas". Pero nada más lejos, porque el centro

cultural no obedece a ley alguna de secuencias cinematográficas, aunque al visitarlo se

sucedan excelentes travellings.

Esta "ciudad ideal" está constituida por seis edificios

asentados sobre un conjunto de plataformas a distintos niveles que se adaptan a los

pliegues del terreno. A sus espacios abiertos se accede mediante un par de trenes que unen

la explanada central, antesala del Museo, con la terminal junto a la freeway. La

gran terraza que da la bienvenida, en la cima, animada por fuentes, arbolado y pérgolas,

está flanqueada por tres pabellones: el auditorio, el centro de información y el

restaurante. Este mismo ritual se repetía al pasar por los propileos, junto a ellos un

conjunto de pórticos daban sombra y resguardo al peregrino que ascendía y llegaba

cansado. |

"Los

Angeles, a city of endless spring, it has got four seasons: earthquake, fire, flood and

drought".

A popular sayingFor some people the Getty Centre, leant on the hills of Santa

Mónica and with the motorway to San Diego winding at their feet, resembles a monastery or

a fortress. It is possible. The most common image of a monastery usually reminds us of a

defensive framework. The monasteries were, in fact, bunkers at their height when they

guarded the wisdom: science and art. The museum complex Centro Getty is no more

than that: a few safes accumulating these properties a millenium later. A centre of art

exhibition and research. Like in those medieval enclosures, you arrive at this centre

through an steep and narrow path which begins in the autopista I-405.

However, it looks more like a greek acropolis with its buildings arranged apparently at

free will, contrasting with the nature of the landscape on opposing its straight and sharp

edges, most of them in cube root. The architects of so many greek temples worked this way,

enclosing, in addition, the sacred area with a perimeter of walls which stemmed from the

bare rock. In a similar way, the Getty Centre, made up of a series of different pavilions

and a garden, stands out over slopes of scabbled travertine in the middle of the scattered

wood. As for a better metaphor, let’s consider the colour and texture chosen by

Richard Meier for the finishing touch: almost marmoreal stone in plinths and prismatic

sizes, granite on the floors and his characteristic brightless white and beige square

plates for the enveloping surfaces. It has intentionally been opted "for a sound

classicism" as a symbolic image so that the dwellings of the twentieth century gods

can settle on the earth. Though the traditional part in the curriculum of this maestro

de obras is his european modernity, focused on the renaissance of his heroic

beginnings.

Whereas the greeks worship their idols in the dispersed temples inside those places of

pilgrimage, the american citizens can admire the european art collection shown in the

different rooms of this "ideal city for the culture". The great Museum that the Grupo

Getty has built, sighting the bay from Malibú to Venice, could be probably a

sanctuary of our times in which art has replaced the Gods in the Olympus. And this is not

a gratuitous remark. In fact, according to Mario Botta, architect of the MoMA in San

Francisco, any museum can be understood "as an space devoted to the search of a new

religiousness". In his opinion, "the museum fulfils in the modern cities a

similar part to that of the cathedral in the past centuries". And the cathedral of

Los Angeles cannot be an isolated milestone like the MoCA of Arata Isozaki or other

museums that are confused in the urban vastness. The cathedral of the most extensive city

in the planet must have another scale, which corresponds to one of an acropolis.

Starting from these conditions (representativeness, location and programme), the Getty

Centre arranges its buildings dotted about on two orthogonal networks, turned each other,

and happens to be a reflection of the two directions the highway takes when it bends under

the enclave: one is the area of Los Angeles, the other is the passage of Sepúlveda. This

subtle reference helps as an excuse the ordered geometry of the cultural complex, where a

collection of architectures is displayed as if it were a three dimensional collage. The

resultant proposal, so absorbed in its casual appearance, may lead someone to think that

Richard Meier has been driven by the Metropolis since, "if the discontinuity is the

urban reality of Los Angeles, the real thing its to design piece-shaped buildings",

Ann Bergren states. But it is far from it, because the cultural centre does not obey any

film sequence at all, although when visiting it, one can enjoy excellent perspectivas.

This "ideal city" is formed by six buildings, settled on a collection of

shelves in different levels and adapting themselves to the folds of the land. You arrive

at these open areas by a pair of trains which link the central esplanade, the anteroom of

the Museum, with the terminal next to the autopista. The lively big terrace at the

top welcoming the visitor, with fountains, trees and rooftop gardens, is flanked by three

pavilions: the auditorium, the information centre and the restaurant. The same ritual is

repeated on walking past the propylaeum, where a group of portals gives shade and

protection to the tired pilgrim who has just climbed. |

Pasaje de acceso a la terminal del tren junto a la autopista /

Entrance passage to rail station beside freeway

Acceso al centro getty: el auditorio./ Entrance to getty

centre: auditorium

Terminal del tren en la explanada central. / Rail station on

central esplanade

Escalinata de acceso al museo / Museum entrance steps

Marquesina de acceso al museo / Museum entrance canopy

Rotonda del vestíbulo / Lobby rotunda

Plaza interior del museo: pabellón colecciones permanentes /

Museum courtyard: permanent collections pavilion

Plaza interior del museo: pabellón exposiciones temporales /

Museum courtyard: temporary exhibitions pavilion

Plaza interior del museo vista desde el vestíbulo de un

pabellón / Museum courtyard seen from a pavilion lobby

Centro de documentación y biblioteca: vista desde el acceso./

Document centre and library: view from entrance

Centro de documentación y biblioteca: vista desde el jardín

de robert irwin / Document centre and library: view from robert irwin garden

Testero sur del museo / South end of museum

Terrazas panorámicas de la cafetería del museo / Panoramic

terraces of museum cafeteria

Talud con jardín del desierto de california visto desde el

interior del museo y desde la rampa con la autopista al fondo / Slope with california

desert garden, seen from museum interior and from ramp with freeway in background |

Hacia

arriba, ascendiendo por la escalinata, se anuncia la entrada al gran vestíbulo del Museo;

en un lateral quedan los edificios administrativos. Tras la marquesina que señala la

puerta, se despliega la potente rotonda acristalada, uniformemente iluminada, con el patio

interior como telón de fondo curvado. Aquí confluyen los ejes de toda la ordenación

urbanística, desde aquí parten los recorridos de visita y desde aquí se despliegan las

cinco cajas que contienen las salas de las colecciones permanentes y el pabellón de las

exposiciones temporales, volúmenes que giran y bailan alrededor de los estanques de una

plaza abierta a los horizontes. De alguna manera, el Museo es al Getty Center lo

que el templo principal de la deidad a la acrópolis: la casa donde residía el dios

protector de la ciudad.

Por último, hacia el océano queda el centro de documentación con la

biblioteca. Se trata de un cilindro vaciado por otro concéntrico y abierto en un

cuadrante. Su forma circular lo dota de autonomía frente al resto del complejo y refleja

el carácter introspectivo de su finalidad: la investigación histórica. Existe cierta

afinidad entre este volumen incompleto y las antiguas tolos, aquellos templos

redondos bajo la advocación de la ciencia aún desconocida. Esta última pieza se separa

y se une a los cubos del Museo y a los porches panorámicos de la cafetería a través de

un jardín en cávea, teatral, lleno de colorido (obra de Robert Irwin), con arbustos y

setos en laberinto, un estanque, la cascada y el riachuelo que surca el bosque (con su

zig-zag) y nace en el surtidor de la cima, próximo a la gran rotonda. Otros jardines del

Centro Getty, más del sur de California, rematan los taludes en círculo de los extremos

norte y sur.

Tras esta descripción, podría intuirse que la visita al Getty Center

puede llevar a confusión, tanto al entendido como el profano, y no es así en ninguno de

los pabellones, ni siquiera en el conglomerado del Museo. Aquí, como en las demás

partes, resulta muy fácil descubrir las perspectivas y la gradación de las secuencias:

basta con dejarse llevar por las circulaciones para disfrutar del espacio interior que se

prolonga en la mirada hacia el paisaje exterior: del propio conjunto y del territorio

circundante. Después de todo la poética de Richard Meier se repite, se refina y se

multiplica: retículas giradas, ordenación en collage, perspectivas estudiadas,

formas abiertas, volúmenes simples, proporciones áureas y composiciones abstractas en

base a una exquisita geometría que se autoalimenta. Y todo ello zurcido por un claro

sistema de recorridos que invita a pasear, descansar y contemplar unos espacios bañados

por una intensa luz blanca perfectamente controlada. Arquitectura exhibicionista que

muestra con delicadeza y privacidad los objetos de la colección. En cualquier caso, como

diría la crítica: "de Meier siempre esperamos un Meier".

Aunque el paralelismo histórico sea fortuito, no se debe olvidar que Roma

sentía una profunda admiración por la cultura griega, por ello adoptó a sus dioses,

para no sentirse huérfana y carente de pasado. Pero los romanos lo tenían todo y mejor:

ciudades ordenadas, grandes infraestructuras y legiones que garantizaban su supremacía.

Richard Meier no es un romano, aunque mentalmente se remonte al tiempo de estos evocando

Villa Adriana con "sus secuencias espaciales, imagen de solidez y sentido del

orden" para asegurarse que construcción y paisaje se pertenecen mutuamente. No lo

es, pero repite sus actitudes y comportamientos de modo blanco y sintético. Quizás el Getty

Center no sea una obra maestra, tal y como vemos la casa Smith, el Atheneum o el Museo

de Atlanta; pero es la obra de un Maestro: sabia y reposada. Todo un clásico.

Ahora bien, habría cabido esperar que este lugar sagrado presentase una

imagen más acorde con la actividad de la ciudad, después de todo, Los Ángeles es La

Meca del cine, el arte de este siglo. Desde sus estudios se han fabricado numerosos mitos

o héroes, aunque no dioses. ¿No habría sido más coherente construir un templo para las

estrellas del firmamento cinematográfico? Erigir en esta ciudad, donde la realidad supera

a la ficción del celuloide, un complejo museístico que idolatra el pasado europeo

equivale, en cierto sentido, a construir un mausoleo además de suponer una afrenta a la

más genuina contribución de la sociedad americana a la Cultura. En este caso, los

dioses, ofendidos, pueden provocar un cataclismo, entre otras cosas. |

As the visitor

goes up the outside staircase, the entrance to the large hall of the Museum is announced;

the administrative buildings lie at one side. The big glass circular gallery, plainly lit

up, is displayed behind the canopy that shows the door, with the inner yard as a bent

backdrop. The centre lines of all the urban planning meet here; the visit routes start

here and the fine boxes containing the permanent collection rooms and the temporary

exhibition pavilion are shown here,volumes that swing and dance round the lakes of an open

square on the horizon. To a certain extent, the Museum represents for the Centro Getty

what it did the main temple of the deity for the acropolis: the house of the protective

god in the city. Finally, the centre of documentation with the library remains towards

the ocean. It is a cylinder emptied by a concentric one and opened in a quadrant. Its

circular shape gives it autonomy as opposed to the rest of the complex and reveals the

introspective character of its purpose: the historic research. There is a certain likeness

between this incomplete volume and the ancient tolos, those round temples dedicated

to the yet unknown science. This last piece is separated and joined to the cubes of the

museum and to the panoramic arcades of the coffee shop through a colourful amphitheatrical

garden (designed by Robert Irwin) with a maze of bushes and hedges, a pond, the waterfall

and stream which spring up in the fountain at the top, cleaving the wood in zigzag, next

to the big circular gallery. Some other gardens in the Getty Centre, south- californian

style, finish off the circular slopes of the north and south ends.

After this description, one might feel that the visit to the Centro Getty can

lead both the expert and the layman to confusion, but it never does in any of the

pavilions, not even in the conglomerate of the Museum. Here, like in the other parts, it

is very easy to find out the perspectives and the gradation of the sequences: it suffices

to be carried away with the circulations for the visitor to enjoy the inner space,

stretching out before him towards the outer landscape: of the own collection and the

surrounding territory. After all, the poetics of Richard Meier recurs, becomes refined and

multiplied: turned networks, a collage arrangement, studied perspectives, open shapes,

simple volumes, golden proportions and abstract compositions on the grounds of an

exquisite geometry which feeds back. And everything is put together by a clear system of

routes that invites the visitor to walk, rest and contemplate the spaces bathed by a

perfectly controlled strong white light. Exhibitionist architecture delicately and

intimately showing the objects of the collection. In any case, "we always expect a

Meier by Meier", as the critic would say.

Although the historic parallelism can be chance, it must not be forgotten that Rome

felt a deep admiration for the greek culture, that is why they adopted their gods, in

order not to feel themselves orphans and without a Past. But the romans had everything

better: planned cities, large infrastructures and legions who guaranteed their supremacy.

Richard Meier is not roman, although he mentally goes back to their times recalling Villa

Adriana with "its space sequences, a solid image and sense of order" to make

sure that the building and the landscape belong to each other. It is not that way, but he

repeats their attitudes and behaviour in a synthetic and white manner. Perhaps the Centro

Getty is not a master piece, as we see the Smith house, the Atheneum or the Museum of

Atlanta, but it is the work of a Maestro: wise and relaxed. A true Classic.

Nevertheless, one would have expected that this sacred place should show an image

according to the activity of the city. Los Angeles is the "Mecca" of the cinema,

the art of this century. Many heroes and myths have been made in these studios, although

they are not gods. Would not have it been more coherent to build a temple for the stars of

the film firmament?. To build in this city, where the reality goes beyond the fiction of

the films, a museum complex which worships the european past is equivalent to build a

mausoleum and, at the same time, it is an insult to the most genuine contribution of the

American society to Culture. In this case, the gods, offended, can bring about a

cataclysm, among other things. |