Comments on university space

| Comentarios

al espacio universitario Comments on university space |

|||

|

|

|

|

| Luis Martínez Planelles | |||

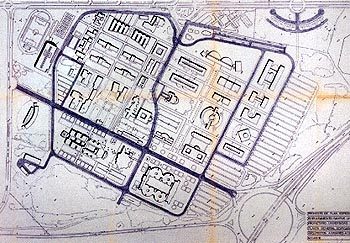

"... A la Naturaleza le

gusta que la transformen con cuidado. Nuestra sociedad, de la que es reflejo la Universidad y viceversa, todavía confiere mayor valor a lo figurativo frente a la abstracción, al ornato frente a la sinceridad, a las formas revestidas de neo-neoclasicismo frente al racionalismo. En nuestro caso resultó controvertido hacer comprender a la Comunidad Universitaria la necesidad de respetar la Torre de Control del antiguo aeródromo de Rabasa, en otro tiempo (todavía reciente) situada extramuros y actualmente centro geométrico del campus. La torre de Control, edificio racionalista del año 40 en consonancia con la arquitectura de las vanguardias europeas, evoca la memoria del lugar donde ya no quedan trazas de los anteriores bordes físicos y culturales. Su posición, de colateral a concéntrica, no queda en la trama adecuadamente recogida debido a que el mecanismo del planeamiento no parte de las preexistencias (léanse hangar y Torre de Control), de su memoria, y por ello no articula adecuadamente estas piezas que por su concepción son de una importancia vital para entender la morfología del campus. De hecho, la tensión concéntrica que genera la torre como elemento puntual y estático no guarda consonancia con el gran eje entre aularios que, por su carácter lineal y direccional, aporta una voluntad dinámica a ese espacio impidiendo a la torre encontrar su posición y su silencio. En sus orígenes, la estructura generadora de la trama universitaria resulta ser las edificaciones del campamento militar anejo a la Torre de Control, el cual se transferiría en los años 70 pasando a denominarse Centro de Estudios Universitarios de Alicante (C.E.U.) y, más tarde, Universidad de Alicante. Dicho campamento es de arquitectura post-racionalista de la misma época que la Torre de Control. Era un sistema pensando desde la repetición (funcionalismo), coherente con su orografía plana, función de los vuelos...La vegetación protegía a la edificación generando un microclima a su alrededor mejorando el control de temperatura y humedad. Estas construcciones, de geometría estricta y orientadas, prácticamente, según un eje Norte-Sur, respondían a una clara jerarquía funcional: Pabellón de Gobierno y Administración, barracones para tropa, edificaciones de servicios y elementos singulares (hangar y Torre de Control). Las tipologías empleadas han permitido resolver de manera muy clara estos edificios consistentes en planta baja más planta alta a modo de Torre (tropa y mandos) y su valía ha quedado contrastada al haberse adaptado con muy pocos cambios tanto a usos docentes como a administrativos o de investigación. Estos pequeños pabellones serían los encargados de dar cobijo y proporcionar conocimientos a las primeras promociones del C.E.U. Esta concepción funcionalista se podía trasladar de manera casi literal a la que precisaba la Universidad a partir de la ley de Reforma Universitaria (L.R.U.) en los años 80 que regulaba su nueva organización interna, reconociendo a las unidades departamentales autogestión financiera y responsables de su investigación y docencia. A partir de este momento, desaparece el modelo de facultad del siglo XIX que responde a un esquema social determinado, planteando una asociación de conocimientos en vez de una agrupación gremial y obligando, así mismo, a una especialización funcional de las edificaciones. De esta forma, la transcripción de esa estructura se traduce, de acuerdo con la anterior, en el edificio de Rectorado y Servicios Generales, edificios de aulas y departamentos, edificaciones para servicios para investigación e institutos universitarios como elementos singulares. Esta descomposición funcional se produce de una manera tan lineal (campamento militar- campus universitario) que también podría haber permitido, por si solo, regulara el crecimiento de la Universidad prolongando adecuadamente su trama; la del campamento militar. Desafortunadamente, la expansión del campus, desde el principio, apostó por el desarrollo de grandes edificaciones sin ningún tipo de regulación ni limitación en su inicio e incapaces por si solas de crear espacio urbano, de crear universidad. Esta expansión de la Universidad resultaba contradictoria con los valores que poseía la trama generadora. En la primera mitad de los 80 se construyen las facultades de Derecho, Ciencias, Historia, Escuela Politécnica, Club Social.... cuya concepción dependería de la Junta de Construcciones del entonces Ministerio de Educación. La escala y la desproporción de las piezas se multiplican. La relación con las construcciones del campamento militar es meramente una cuestión cardinal, de orientación de las piezas. De hecho la llamada plaza de la Universidad representaba únicamente una voluntad semántica puesto que el gran vacío resultante se entiende más como un espacio de carácter residual que con voluntad de congregación. No se consigue recuperar ese equilibrio entre edificación y espacio verde que se observa en la zona antigua donde las masas de árboles tienen proporciones similares a los elementos construidos. En el año 86 se elabora el proyecto del arquitecto-urbanista Enrique Jiménez que propone un esquema concéntrico con un centro universitario rodeado por un anillo de pequeñas construcciones departamentales e institutos protegidos, a su vez, por un espacio verde. Una aportación fundamental supondría la configuración y posterior construcción del nudo de la autovía puesto que, aunque no se respetó su diseño original de incluir entre otras cuestiones un museo al aire libre en su interior, modifica la forma de acceso - y de lectura - al campus y consigue reducir a muy poco tiempo la comunicación desde la ciudad o desde cualquier otro núcleo periférico. Otra cualidad de ese trabajo es que intentaba condicionar a la futura arquitectura desde un cierto rigor tipológico que habría sido necesario para evitar que el campus se hubiera tansformado en un catálogo-muestrario de arquitecturas. Una última cuestión de dicho plan, más profética, era el planteamiento plurinuclear (varios campus) con un rectorado emplazado en la ciudad, caso de la Universidad de Valencia, como garantía de gobernabilidad de los diferentes campus, no de independencia. Con todo, resultó la primera Universidad del país que planteó su crecimiento adaptado a la nueva ley de Reforma Universitaria, inaugurando con el plan su autogestión y autonomía universitaria y posibilitando el compromiso de recursos económicos. Sin embargo, esta plan, al margen de alguna actuación muy puntual, no sigue adelante. Este modelo de planteamiento se sustituye por el redactado por los arquitectos Alfonso Navarro y Alfonso Casares el cual intenta resolver desde la edificación la creación del espacio público apoyándose en una cuadrícula generada a partir de la estructura militar inicial, asumiendo las nuevas construcciones pero sin mantener la escala. Se construyen en esta fase (2ª mitad de los 80)cl 1º Aulario, la Facultad de Económicas, la Escuela de Enfermería, Escuela Politécnica,... grandes unidades, con ejes de simetría en su composición pero dispuestas contradictoriamente de forma axial al eje principal. De carácter isótropo en un entorno que no lo es. A principios de los años 90 se redactan las Guías de Diseño para ordenar lo que sería la 3ª fase de crecimiento del campus hasta la colmatación de éste. Desarrolladas por el equipo de urbanistas Taller de Ideas plantean, desde un punto de vista más disciplinar, un esquema propositivo y no reglado que se fundamenta en una malla estructurada en base a la creación de nodos de interés, la cual persigue esa idea subliminar de campus unitario que los otros planes no consiguen. Corresponden a esta etapa de los edificios de Aulario II, Museo Universitario, Centro de Servicios, Biblioteca General, Escuela Politécnica III, Edificio de Institutos, Escuela de Óptica, Edificio Departamental de Ciencias Sociales y Centro de Creación de empresas, la mayoría de ellos a través de concursos y con arquitectos en las comisiones asesoras de la talla de Juan Navarro Baldeweg, A. Siza, W. Curtis, José Llinas, Victor Rahola, Gabriel Ruiz Cabrero, Emilio Gimenez, Vicente Vidal, Alberto Campo Baeza, Jose Antonio Corrales... consiguen una arquitectura de calidad dentro de una heterogeneidad responsable. El espacio urbano configurado resulta demasiado formal y en determinados casos de escala excesiva como algunos edificios que lo sustentan. Parece sorprendente, por lo vertiginoso, la capacidad de modificar el paisaje, de urbanizar, de crear paisaje urbano. Finalmente el edificio de Rectorado y Servicios Generales, del arquitecto A. Siza, consigue con maestría integrar arquitecturas y urbanización aportando serenidad al conjunto a través del reflejo mate de sus muros blancos. Al final, el esquema resultante plantea ciertas difusiones puesto que, el espacio intersticial entre las edificaciones, el espacio en negativo como generador de relaciones y, lo que es más importante, como soporte del carácter público del espacio, queda de alguna manera difuminado en beneficio de la mayor facilidad de gestión que representan estas unidades edificatorias autónomas y se confía a la arquitectura la configuración de esa cualidad espacial que el urbanismo no resuelve. Sin embargo, podríamos pensar que el verdadero problema consiste en que este modelo, que ha conllevado importantes inversiones en el mundo universitario en estos últimos 10 años, ha sido el único que, además de en la Universidad de Alicante, ha sido utilizado como base de partida en experiencias tan próximas como la ampliación de la Universidad de Valencia en el Campus de los Naranjos, la ampliación de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, la creación de la Universidad de Miguel Hernández de Elche, la configuración de la Universidad Jaime I de Castellón y la del Campus de Espinardo de la Universidad de Murcia, donde la potencia y autonomía de los edificios perfectamente configurados contrasta con unos instrumentos de ordenación urbana o inexistentes o posteriores a la creación de esos edificios, resultando dicho espacio público como aquel que, tan sólo, no es ocupado por la edificación. Podríamos considerar que el espacio urbano universitario está todavía por debatir. |

"...Nature likes to be

transformed with care. Our society, of which the University is a reflection and vice-versa, places even greater value on the figurative than on the abstract, on ornament than on sincerity, on forms cloaked in neo-classicism than on rationalism. In our case, it was quite a delicate matter to make the academic community understand the need to spare the control tower of the old Rabasa aerodrome, which until recently was outside the city and is now the geometric centre of the campus. The control tower, a rationalist building dating from the ‘40s, in line with European avant-garde architecture, evokes memories in this place where no traces remain of former physical and cultural boundaries. Its position has shifted from collateral to concentric and is not adequately reflected in the layout because the planning process did not take the pre-existing memory (the hangar and the control tower), as its starting point and therefore did not articulate these pieces adequately, even though their concept is of vital importance if we are to understand the morphology of the campus. The concentric tension generated by the tower as a reference point and as a static element bears no relation whatsoever to the great axis on which the lecture room buildings lie, which, due to its linear and directional character, gives a dynamic volition to this space that prevents the tower from encountering its proper position and its silence. The origins of the structure that generates the university’s layout are the buildings of the military base adjoining the control tower. It was transferred in the ‘70s to what later became the University of Alicante but was originally called the Centre of University Studies of Alicante (Centro de Estudios Universitarios de Alicante or C.E.U.). The architecture of the base is post-rationalist and dates from the same period as the control tower. It was a system based on repetition (functionalism), coherent with the flat terrain, its flying-related function, etc. The buildings are protected by vegetation which generates a micro-climate around them, regulating the temperature and humidity. These buildings, with their strict geometry laid out essentially on a north-south axis, were arranged according to a clear functional hierarchy: Command and Administration block, barracks for the troops, service buildings and single elements (hangar and control tower). The building types provided these constructions with a very evident solution, ground floor and tower-type upper floor (troops and officers), and their value was confirmed by the very few changes that were necessary to adapt them to teaching uses as well as to administration or research. These small blocks were those which provided shelter and imparted knowledge to the first graduates of the C.E.U. It proved possible to transfer this functional concept almost literally to the changing needs that followed from the University Reform Act of the ‘80s, which regulated the internal organisation of the universities and devolved on each department the responsibility for its own financial management, research and teaching. The 19th century faculty model, which had responded to a particular social set-up, disappeared from this moment: knowledge-based groupings replaced corporate groupings and functional specialisation of the buildings became necessary. The physical translation of this structure was in consonance with the previous structure, transformed into the Rector’s (Vice-Chancellor’s) offices and General Services building, lecture room and department buildings, service buildings for research and the university institutes as singe elements. This functional breakdown is so linear (military camp – university campus) that it would have been sufficient by itself to regulate the growth of the University through an appropriate extension of its layout, that of the military base. Unfortunately the expansion of the campus, from the start, opted to develop large buildings, without any kind of regulation or limitation to begin with, which by themselves were incapable of creating an urban space, of creating a university. The University’s expansion was in contradiction with the values that the original layout had possessed. Built during the first half of the ‘80s, the concept of the Law, Science and History faculties, the Polytechnic School, the Social Club [Union] etc. was laid down by the Ministry of Education’s Constructions Committee. The scale and lack of proportion of the buildings multiplied. Their relationship with the buildings of the military base is purely a question of cardinal points, of the direction in which they face; the so-called University Square denotes nothing more than the semantic will for one, as the great resulting vacuum has more of a residual space than of any intention of constituting a gathering-place. They fail to recover the balance between the buildings and the green space of the old part, where the groups of trees are of similar proportions to the buildings. In 1986 the architect and urbanist Enrique Jiménez drew up a project for a concentric plan, with a university centre surrounded by a ring of small department and institute buildings which, in turn, would be protected by a green belt. One of his fundamental contributions was the design and subsequent construction of the dual carriageway junction. Although the original plans (which included, amongst others, an open-air museum in its interior) were not followed, it changed the mode of access – and the reading – of the campus and made the travel time from the city and from other peripheral nuclei very short. Another feature of this work was that he tried to determine the future architecture of the campus with a certain degree of the typological rigour it would need in order not to become a catalogue or sampler of different architectures. A last, more prophetic, aspect of his plan was a pluri-nuclear approach (several campuses), with the Rector’s (Vice-Chancellor’s) office in the city centre, like Valencia University, to guarantee the governability rather than the independence of the various campuses. Nonetheless, Alicante was the first university in Spain to postulate adapting its growth to the new University Reform Act. The 1986 plan inaugurated Alicante’s self-management and autonomy as a university and the possibility of its committing financial resources. However, apart from a few isolated aspects, this plan was dropped. Its approach was replaced by that drawn up by the architects Alfonso Navarro and Alfonso Casares, which tried to solve the creation of public space through construction, based on a grid that took the original military structure as its starting point and accepted the new buildings but abandoned their scale. During this period (second half of the ‘80s), Lecture room block I, the Economics Faculty, the Nursing School, Polytechnic School II etc. were built. They are large units. Their composition contains axes of symmetry but they are arranged in a contradictory manner, axially to the main axis. Their character is isotropic in surroundings that are not. At the beginning of the ‘90s, Design Guidelines were drawn up to regulate what was to be the 3rd growth phase of the campus until this became saturated. These guidelines, developed by the urbanist team Taller de Ideas, outline a plan that is more propositional than regulatory, from a more disciplinary perspective, based on a grid which is structured around the creation of nodes of interest, in pursuit of the subliminal idea of a unitary campus that the other plans had not achieved. The buildings from this period are Lecture room block II, the University Museum, the Services Centre, the General Library, Polytechnic School III, the Institutes Building, the Optics School, the Social Sciences Department Building and the Business Creation Centre, most of which were awarded by public competition, with the advisory committees including architects of such stature as Juan Navarro Baldeweg, A. Siza, W. Curtis, José Llinas, Victor Rahola, Gabriel Ruiz Cabrero, Emilio Giménez, Vicente Vidal, Alberto Campo Baeza or José Antonio Corrales. They achieve an architecture of quality within a responsible degree of heterogeneity, but their urban space is too formal and in certain cases the scale is excessive, like some of the buildings on which it is based. It seems surprising just how fast the landscape can be changed and urbanised, how an urban landscape can be created. The latest work is the Rector’s (Vice-Chancellor’s) office and General Services building by the architect A. Siza, which integrates different architectures and urban planning masterfully, bringing serenity to the whole with the matt gleam of its white walls. In the end, the resulting plan gives rise to certain diffusions because the spaces between the buildings, the space in negative as generator of relationships and, more importantly, as the medium of the public character of space, is toned down to a certain extent in favour of the greater ease of management represented by the autonomous building units. Architecture has been given the task of configuring the spatial quality that has not been resolved by urban planning. Nonetheless, the real problem may be that this model, which has meant heavy investment in the academic world over the past 10 years, has been the only one. As well as Alicante University, it has been used as the starting point for experiences as close to us as Valencia University’s expansion to the Naranjos campus, the Polytechnic University of Valencia extension, the creation of Miguel Hernández University in Elche, the shape of Castellón’s Jaime I University and that of the University of Murcia’s Espinardo campus, where the power and autonomy of perfectly configured buildings contrast with urban organisation tools that are either non-existent or arrived after the buildings, so that public space is merely that which is not occupied by buildings. We might well consider that university urban space is a subject which has still to be discussed. |

|