Castellon Art Museum. Castellón

MANSILLA + TUÑÓN, arquitectos

Emilio Tuñón, Luis Moreno Mansilla

Premio COACV 1999-2000/1999-2000 COACV Prize

Obras de arquitectura/Works of architecture

| Museo

de Bellas Artes. Castellón Castellon Art Museum. Castellón |

||

| Arquitectos/Architects: MANSILLA + TUÑÓN, arquitectos Emilio Tuñón, Luis Moreno Mansilla |

|

|

|

|

| COFRE

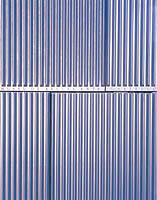

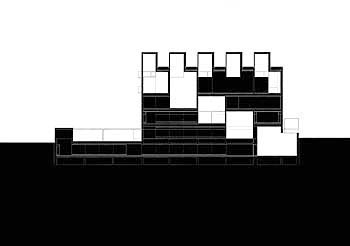

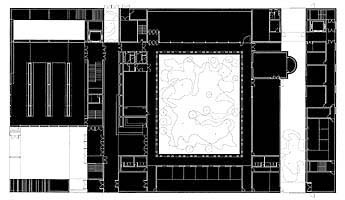

DEL TESORO, CAJA DE CAUDALES

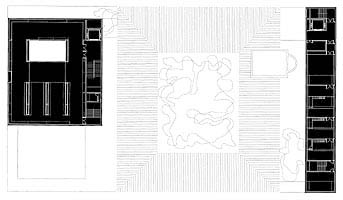

Mientras en la manzana anterior los edificios de vivienda se entretienen, banales, en gestos conocidos, la pared gris del Museo, silenciosa y absoluta, convierte el plano de la alineación en un acontecimiento urbano, y de su severidad herreriana tan sólo se liberan, parcialmente, las alturas, los volúmenes en rediente que anuncian rayados los lucernarios de la cubierta. Pues el material -el aluminio colado- presenta la nobleza y la indiferencia que en el clasicismo herreriano tenía la piedra berroqueña. Una materia elegida por su perfección, por su calidad, no tanto por sí misma, y cuya severidad algo brutal no renuncia a constituirse también como soporte de un sutil y evidente refinamiento. Pero antes de llegar a la esquina, y siguiendo -imagino- el trazado del viejo colegio, el edificio, cortés, se vacía para dar paso a una plaza que ocupa aquélla, mientras el volumen gris, según dobla, adquiere una composición moderna, racionalista, que se reviste, algo más amable, de gestos sotianos; gestos acaso inadvertidos y que parecen propios de una manera común, de un elegante y acostumbrado vicio colectivo. Uno pasa el umbral y enseguida puede comprender, a poco que ande, que el trazado del humilde colegio ha facilitado un orden largo y tranquilo de las dimensiones, una lenta extensión horizontal impuesta por el gran rectángulo del sencillo claustro, y que suele ser ajena a los edificios modernos. Dentro, la severa obsesión metálica inicia su desaparición, y si uno puede entretenerse en la sala de exposiciones o en la lograda biblioteca, no ha de tardar mucho en entrar en aquel importante volumen que, como un inmenso templo castellano, o como una gigantesca -metálica- caja de caudales, anuncia y encierra el tesoro. El tesoro del contenido del Museo, desde luego, y otro tesoro más, el espacial que lo alberga, que ha de ser custodiado tan sólo por la memoria, pues este segundo -ya continente, pero convertido a su vez en contenido- se resiste a penetrar en la fotografía si no es en detalle, haciéndolo con esa indiferencia y con ese sabor antiguo de quien reserva celoso para los visitantes el placer completo de un edificio. En él toda severidad herreriana ha desaparecido. El cofre berroqueño y metálico se transforma en blancos, en colores y en maderas, y aquella opacidad que no permitía averiguar otra cosa que su rigurosa y firme custodia se ha vuelto transparente, permeable, sutil, fingiendo con eficacia que enseña el tesoro de una vez, aunque lo haga en realidad por partes. Y conduciendo al visitante en una lenta, cenobial, ascensión que le permite registrar la totalidad mediante la vista diagonal que todo lo alcanza y que exhibe la ilusión de encontrarse uno ubicuamente en cada uno de los sitios. Cuesta bajar cuando se alcanza el cenit, pues la luz del Levante, matizada pero poderosa a través de los cúbicos lucernarios -y la mirada, que puede ahora bajar su punto de vista y descansar, perezosa- invitan a acodarse contra una de las barandas y contemplar pausados el espacio por el que ascienden, lejos y cerca, los visitantes. Si se miran las plantas se ve la serena ocupación de la manzana, y como así racionalismo radical y arquitectura de la tradición corriente alcanzan un pacto absoluto, sin fricción ni concesiones. La planta tiene una serenidad casi balsámica, una serenidad sin tiempo, tan clara como si no tuviera alternativa, producto de un orden claustral tan eficaz como evidente. Secciones y dibujos de alzados, como en de la Sota, hacen trampas: no todo es tan ligero, claro, sin matices, liviano. Los dibujos explican, sí, como la construcción se va a esforzar para lograrlos, para que la materia se transforme y domestique en pos de la idea, presa en ellos. Pero el camino estará lejos de ser inmediato, sencillo, obvio, y el esfuerzo quedará expresado en la apretada solidez del material externo, y se deshará en múltiples y afortunados matices en los interiores. Por suerte, el edificio no es como alzados y secciones prometen, sino mucho más denso, mucho menos obvio, mucho más brumoso y elaborado. Al salir uno piensa si será éste el mejor edificio del siglo XX -cien años- o del XXI -tres meses-, pues hay en él una continuidad moderna que lo acerca a los años heroicos, aquéllos en que los genios que tan oportunamente nacieron asombraron al mundo con sus cúbicas y blancas promesas, paraísos soñados y nunca vividos que permanecen en el olimpo de los deseos. Es un museo racionalista, que no tiene empacho en utilizar los medios limitados y sutiles de nuestros gloriosos antepasados, pero que ya no es blanco, pues, como las catedrales, ha elegido desde el principio revestirse de una pátina gris, de una severidad herreriana que no habla tanto de un mundo feliz y futuro como de un presente no tan nítido, difícil e inquieto. Es un edificio del clasicismo moderno, de una arquitectura que reconoce el lenguaje puro que, otorgado por los dioses, nunca ha envejecido. Que no puede envejecer si uno es capaz de verlo, una vez más, como si acabara de ser inventado, como si uno mismo, incluso, lo hubiera ideado: como si ignorara sus reglas y al descubrir que no las tiene y que es preciso averiguarlas de nuevo, cogiera entre sus manos geometrías aún vírgenes, formas apenas nacidas, detalles inéditos. Tiene hoy Castellón de la Plana una catedral laica, gris, indiferente en su monumental simplicidad al molesto barullo de la ciudad doméstica. Una catedral que, como todas ellas, encierra un tesoro, material y espacial. Una catedral silenciosa, casi adusta, brutal, que no abre su interno esplendor más que aquél que acepta su mutismo y se atreve a comprobar si hay o no luz en aquel sólido cofre, si hay grano en aquel granero, si hay vida en aquella severa caja de metal. Caja acaso de caudales, caja de ilusiones, que pide la fe y el instinto de aquél que no la confunde, de aquél que sabe ver, o, si no, adivinar. Antón Capitel

|

TREASURE

CHEST, STRONGBOX

While the blocks of flats in the block before tritely dally with well-known gestures, the grey wall of the Museum, silent and absolute, makes the frontage an urban event. Only the heights, the striped redans that herald the skylights on the roof, are free, in part, from its Herrera-like severity. The material - cast aluminium - has the majesty and indifference conveyed by the granite of Herrera's classicism. It is chosen for its perfection, its quality, rather than for its own sake. Nevertheless, its somewhat brutal severity does not prevent it being the medium of a subtle, evident refinement. However, before reaching the corner, following - I imagine - the line of the old school, the building courteously draws back to make room for a square on the corner. As it turns in, the grey volume acquires a modern, rationalist composition which, slightly more amiably, has de la Sota-like touches, possibly unconsciously since they seem to belong to a common manner, an elegant, habitual collective vice. As one crosses the threshold, after walking only a short way one realises that the layout of the humble school proffered the long, tranquil ordering of the dimensions, a slow horizontal length, imposed by the great rectangle of the simple cloister, that is not usually found in modern buildings. Within, the severe obsession with metal begins to disappear and if one can dawdle in the exhibition hall or the well-conceived library it is not long before one is admitted into the large volume which, like an immense Castillian church or a giant - metal - strongbox, holds and proclaims its treasure. The treasure is, of course, the contents of the Museum, but also another treasure: the spatial treasure that holds it, which can only be held in the memory as this container that is also content refuses to enter a photograph except in detail. It does so with the indifference and ancient air that jealously reserves the full pleasure of the building for those who visit it. Within, all the Herrera-like severity has disappeared. The granite and metal chest is transformed into whites, colours and woods and the opacity that let nothing be discovered other than its strict, firm custody has become transparent, permeable and subtle, efficiently pretending that it is showing all the treasure at once although in fact it is doing so step by step. It leads the visitor in a slow, monastic ascent that enables the whole to be inspected in a diagonal view that embraces everything and gives the exciting impression that one is in each place, ubiquitous. On reaching the top it is hard to go back down: both the light from the east, powerful despite being filtered through the cubic skylights, and the eye, which can now look down and rest lazily, invite one to lean against the railings and slowly contemplate the space through which, far and near, visitors are climbing. Looking at the floor plans one can see how serenely the block is occupied and how radical rationalism and architecture in the ordinary tradition thereby achieve an absolute pact with no friction or concessions. The floor plan has an almost balmy serenity, a timeless serenity, as obvious as if there were no alternative, the product of a monastic order that is as effective as it is clear. Sections and elevation drawings, as in de la Sota, play tricks: not everything is quite so light, clear, devoid of nuances and weightless. The drawings certainly explain how the building has to strive to reproduce them, to transform and domesticate the material in pursuit of the concept that they capture. But the path is far from immediate, simple and obvious. The effort is expressed by the tight solidity of the external material and disintegrates into a multiplicity of effective nuances in the interiors. Fortunately, the building is not what the elevations and sections augur but far more dense, far less obvious, far more misty and intricate. As one leaves one wonders whether this might not be the best building of the 20th century - a hundred years - or the 21st century - three months into it. It has a continuity with modernism, a closeness to the heroic years in which the geniuses who were born so opportunely astonished the world with their cubic white promises, their dream paradises, never lived, that remain in the Olympus of wishes. This is a rationalist museum that unabashedly uses the limited, subtle means of our glorious forebears but is no longer white as, like cathedrals, it chose from the start to acquire a grey patina, a Herrera-like severity that does not so much speak of a future world of happiness as of a difficult, restless, none too clear present. It is a work of modern classicism, of an architecture that recognises the pure language given by the gods that has never grown old. It cannot grow old if one is capable of seeing it, once again, as though it had just been invented, or even as though one had thought it up oneself, as though one were unaware of its rules and, on discovering that it has none and that they need to be discovered anew, had taken into ones hands still virgin shapes, newly born forms, hitherto unknown details. Castellón now has a grey lay cathedral, indifferent in its monumental simplicity to the irksome confusion of its home city. Like all cathedrals it holds a treasure, both material and spatial. This noiseless, almost harsh and brutal cathedral only shows its internal splendour to those who accept its silence and dare to find out whether or not there is light in that solid chest, whether there is grain in that granary, whether there is life in that severe metal box. This box that may hold wealth, this wonderful box of illusions, demands the faith and instinct of those who do not mistake it, who know how to see or at least guess. Antón Capitel |

|

Antón Capitel es Doctor Arquitecto,

Catedrático del Departamento de Proyectos Arquitectónicos de la

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM), Subdirector de la Escuela

Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid (ETSAM),y Director de la

revista "Arquitectura" del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de

Madrid (COAM).

Es uno de los críticos más reputados del panorama nacional, ha escrito multitud de libros, y artículos en revistas especializadas, y ha sido el comisario de la exposición "Arquitectura del siglo XX en España" en el Deuthsches Architektur-Museum para la Expo 2000 de Hannover. Antón Capitel, PhD Architecture, is professor of the Department of Architectural Design at the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), deputy director of the Higher Technical School of Architecture of Madrid (ETSAM) and editor of Arquitectura, the magazine of the Official College of Architects of Madrid (COAM). He is one of the best-known architecture critics in Spain, has written many books and articles for architecture journals and was the organiser of the 20th Century Architecture in Spain exhibition at the Deutsches Architektur-Museum for the Expo 2000 in Hannover. |

|

|